Common wisdom has it that the four canonical gospels were written before the end of the first century. Mark was written first, then Matthew and Luke, then John. But there are reasons for thinking this picture of things is incomplete or even naive.

M. David Litwa has recently made a case for the late dating of the canonical gospels and Acts of the Apostles in his Late Revelations. In this post, I’m going to present a part of his case.

Litwa proposes two theses:

The gospels were not written all at once but rather in stages.

The gospels were finalized in the middle of the second century.

These ideas can be defended as follows.

It’s a commonplace of modern scholarship that the Gospels according to Matthew and Luke make use of the Gospel according to Mark. But there are at least a few passages where it seems that a passage appearing in the Gospel according to Mark was written after the corresponding passage’s composition in one of these other gospels.

If we say that the canonical gospels were composed in stages and not all at once, there is no problem. In at least some cases, a redactor or editor of Mark’s Gospel expands upon a passage he finds paralleled in Matthew or Luke.

Consider the story of the healing of Peter’s mother-in-law (Matt. 8:14–15; Mark 1:29–31; Luke 4:38–39). Mark’s version is longer and “better dressed” as a piece of narrative than the parallels in the other gospels.

Matt. 8:14 Καὶ ἐλθὼν ὁ Ἰησοῦς εἰς τὴν οἰκίαν Πέτρου εἶδεν τὴν πενθερὰν αὐτοῦ βεβλημένην καὶ πυρέσσουσαν· 15 καὶ ἥψατο τῆς χειρὸς αὐτῆς, καὶ ἀφῆκεν αὐτὴν ὁ πυρετός, καὶ ἠγέρθη καὶ διηκόνει αὐτῷ.

Mark 1:29 Καὶ εὐθὺς ἐκ τῆς συναγωγῆς ἐξελθόντες ἦλθον εἰς τὴν οἰκίαν Σίμωνος καὶ Ἀνδρέου μετὰ Ἰακώβου καὶ Ἰωάννου. 1:30 ἡ δὲ πενθερὰ Σίμωνος κατέκειτο πυρέσσουσα, καὶ εὐθὺς λέγουσιν αὐτῷ περὶ αὐτῆς. 1:31 καὶ προσελθὼν ἤγειρεν αὐτὴν κρατήσας τῆς χειρός· καὶ ἀφῆκεν αὐτὴν ὁ πυρετός, καὶ διηκόνει αὐτοῖς.

Matt. 8:14 And Jesus coming to the house of Peter saw his mother-in-law laid out and feverish. 8:15 And he touched her hand, and the fever left her, and she arose, and she was serving him.

Mark 1:29 And immediately leaving the synagogue they came to the house of Simon and of Andrew alongside James and John. 1:30 Now, the mother-in-law of Simon was lying down feverish, and immediately they spoke to him about her. 1:31 And going to her he raised her taking her by the hand, and the fever left her, and she was serving them.

Comparing the two passages in this way, we can see that the version in the Mark is clearly more developed than that of Matthew. Mark takes over a few words from Matthew (those in bold), changes a few for his own purposes (those in italics), but also simply adds more of his own.

At the same time, there are instances where Matthew seems clearly to be later than Mark. This can be seen in cases where Matthew seems to correct errors in Mark.

For example, Matt. 3:3 corrects Mark 1:2–3 which attributes to Isaiah a prophecy which actually appears in another OT text altogether. Mark 2:26 has Jesus incorrectly name Abiathar as the high priest in the time of David. Matt. 12:3 removes the error altogether. Matt. 14:1 correctly refers to Herod correctly as a “tetrarch,” not incorrectly as a “king” as in Mark 6:14, 22.

If you think that Mark and Matthew had to be written all at once, then this is a mysterious situation indeed. How could one make use of the other, if one has to be written in its entirety before the other? But if you think that the gospels were written in stages, then there’s no trouble at all. An editor of Matthew makes corrections on an earlier stage of Mark while drawing from that text, and a later editor of Mark develops the text further, beyond the version that the Matthean editor had access to.

It would take a lot of work to provide further examples of this. I’ll have to save that for another day. Let these few examples suffice to show that support can be given for Litwa’s thesis that the gospels were written in stages, not all at once.

If the gospels were written in stages and not all at once, that means that they cannot be dated easily to any one point in time. There may be material in them that is quite early, dating to the first century. That does not mean that the final form of any gospel was written in the first century. The finalization of the gospel may have even happened much later, for example in the second century.

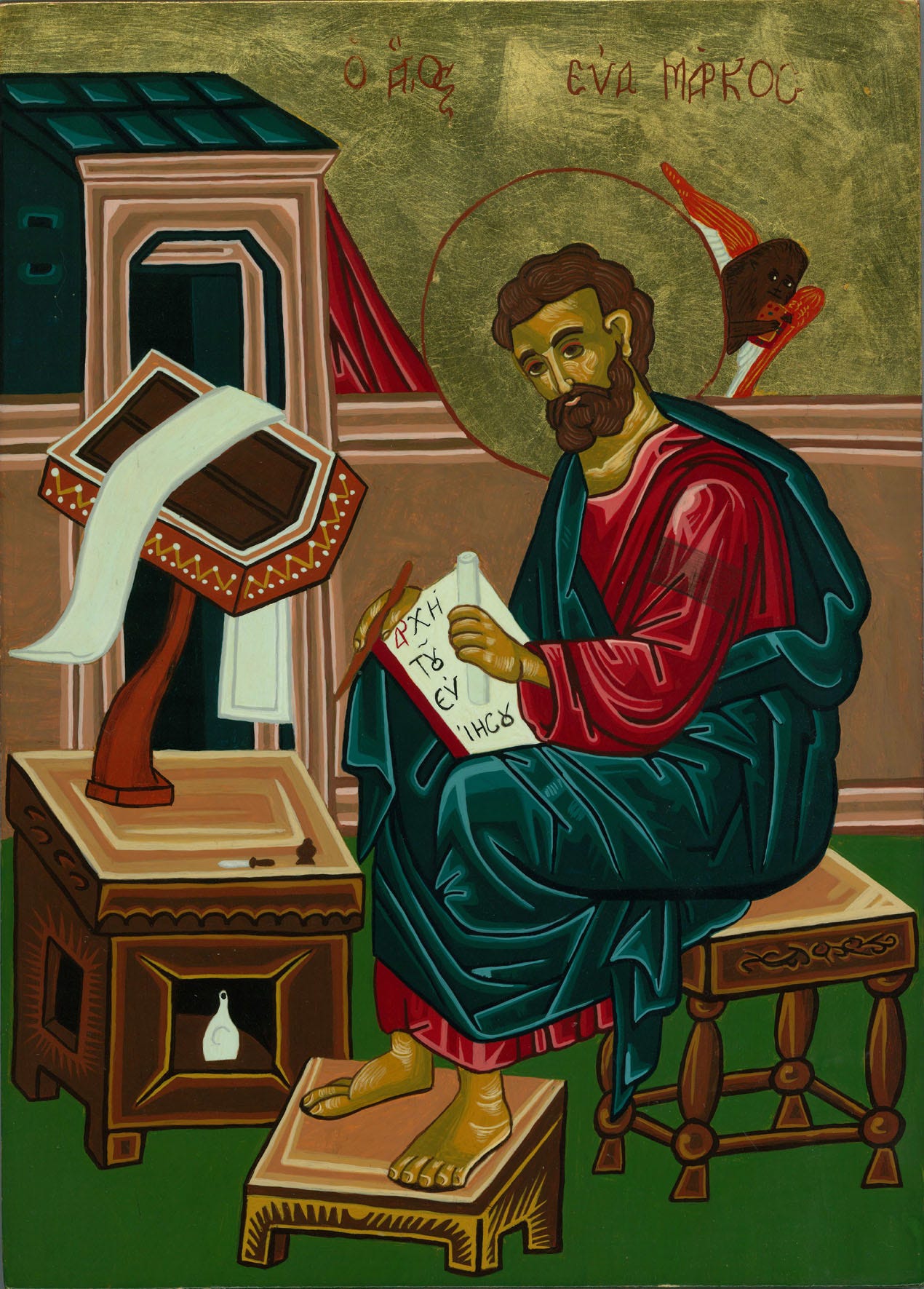

I’ll limit myself once more to Mark’s Gospel. By way of an argument for the finalization of the Gospel according to Mark in the second century, Litwa gives a number of arguments.

Mark 13:2 references the destruction of the Temple. This only provides a lower limit of around 70 CE for the dating of the gospel, not an upper limit.

The rise of “nation against nation” and “earthquakes” (13:8) does not describe the situation in Jerusalem around 70 CE. But there was a very famous earthquake in Antioch on December 13th, 115 CE.

The persecution of Christians by “governors and kings” (13:9) is unlikely as a description of the situation of Christianity in the first century. Pliny wrote a famous letter (Epistola 96) to the emperor Trajan about what to do with certain persons called “Christians.” Pliny only knew what he did by interviewing a few of them. If there had been precedent of Christian interaction with high-ranking officials in Roman government, presumably Trajan and Pliny would have known about it.

The phrase “abomination of desolation standing” (13:14) must be interpreted. It is a neuter noun (τὸ βδέλυγμα τῆς ἐρημώσεως) paired with a masculine participle (ἑστηκότα). This would make sense if it referred to the statue of a god or emperor placed by Hadrian in the rebuilt Jerusalem or Aelia Capitolina around 130 CE.

The instruction for the people who see the “abomination of desolation standing” to “flee to the mountains” (13:14) makes no sense if the situation envisaged by Christ’s words were the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE. That would mean fleeing straight into the weapons of the surrounding armies.

For all these reasons, Litwa concludes that a final date of around 130 CE is most likely for the Gospel according to Mark.

This seems to me to be a very powerful and evidentially satisfying approach to these questions. The assumption that the gospels had to be written all once not only creates insurmountable problems having to do with the determination of the order in which they written, but also seems not to line up with the external evidence.

Irenaeus (ca. 180 CE) says that there are four gospels. He even knows a story about their origins. After Jesus’s resurrection, the apostles received power and “perfect knowledge” from on high and went about preaching the same message in all the corners of the earth. Matthew wrote his gospel in Hebrew, Mark in Greek after listening to Peter, Luke after listening to Paul, and John wrote his own gospel in Ephesus (Against Heresies 3.1.1–2). The apostles then appointed bishops in all the churches as their successors, “delivering up their own place of government” (3.3.1; emphasis added).

No one before Irenaeus says there are four gospels. Justin Martyr (ca. 150 CE) is aware of “memoirs called ‘gospels’” that were supposedly composed by the apostles (First Apology 66) but doesn’t say how many or by whom. His Jewish interlocutor Trypho speaks of a singular “so-called gospel” of the Christians with many difficult precepts in it (Dialogue with Trypho 10). Justin later cites one saying of Jesus’s that isn’t found in any extant text (Dialogue 47) and another that appears in Matthew’s Gospel (Dialogue 100; Matt. 11:27). Justin elsewhere cites a line which also appears in John’s Gospel (First Apology 61; John 3:3). He never cites a gospel text by its title, nor mentions any apostles or bishops by name.

The Epistle of Barnabas and Epistle to Diognetus contain lofty theologies about Jesus that don’t come from Jesus himself. Barnabas only explicitly cites Jesus once (7:11), a citation of unknown origin about something unrelated to its principal subject matter. Though it makes occasional references to writings (e.g., 4:14), it doesn’t name any gospels, apostles, or bishops. Diognetus mentions the “faith of the gospels” and “tradition of the apostles” (11:6) but doesn’t name any gospel or apostle. The Apology of Aristides 2 from the time of Hadrian (117–138 CE) speaks of a singular gospel text, as does the Didache (8:2, 15:3–4).

Papias of Hierapolis (ca. 130 CE; referenced in Eusebius, Church History 3.39) confesses to having disregarded the texts circulating in his time, preferring oral traditions from persons who had heard Jesus’s disciples. But a canonical text simply qua canonical is certainly as good as any oral tradition, if not better. Papias’s words thus suggest there was no canonical “New Testament” in his circles. He knows a tradition that Mark became Peter’s interpreter and wrote down his teachings, though out of order. He’s also heard that Matthew wrote down the “oracles of the Lord” in Hebrew. But the “Mark” mentioned by Papias is certainly not the canonical Gospel according to Mark. Papias’s “Mark” isn’t orderly, whereas canonical Mark is precisely orderly, proceeding from Christ’s baptism to Galilee to Jerusalem to the crucifixion. As for the Hebrew text of “Matthew,” this was apparently an obscure text distributed in the absence of its author or any authoritative commentators, since Papias remarks that “each one interpreted [it] as he was able.” Papias doesn’t know of gospels by Luke or John or any Acts of the Apostles.

Celsus (ca. 175 CE) presents a Jew as arguing that some Christians remold the gospel (singular!) from the original text (singular!) in three ways, and in four ways, and in many different ways, reworking it in order to deny criticisms (Origen, Contra Celsum 2.27). Origen also occasionally seems confused to read Celsus speak of ideas appearing in the canonical gospels inaccurately and as though they were competing oral traditions (e.g., 1.62; 5.56). Celsus may well have proposed arguments gathered from sources that pre-dated the composition of further gospels beyond Mark.

It takes a very long time before we have clear evidence of four canonical gospels attributed to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. If one accepts the majority view regarding the dates of the gospels, this means that around 100 years had passed before anyone ever bothers to name a single one of the gospels. This external evidence coheres far better with the thesis that the gospels were not written all once but in stages, that the editors of the gospels knew of each other’s works and built upon them, and that the final forms of the gospels did not come about until well into the second century.

As for when the various “stages” of composition began, that is a controverted question. I’m inclined to think that the gospels multiplied from one to many around the time of Marcion’s publication of his Testamentum. I incline toward David Trobisch’s theory that Marcion’s publication of his canon led to the effort toward an “orthodox” counter-canon by his enemies. But that’s a discussion for another time.